Sayge Carroll wears a lot of hats: They’re well known in the Minneapolis arts scene as a co-founder of Mudluk Pottery, a prolific visual and public artist, and a committed community organizer. The newest project to have their name attached to it went up late this winter in Seward, just south of Downtown Minneapolis.

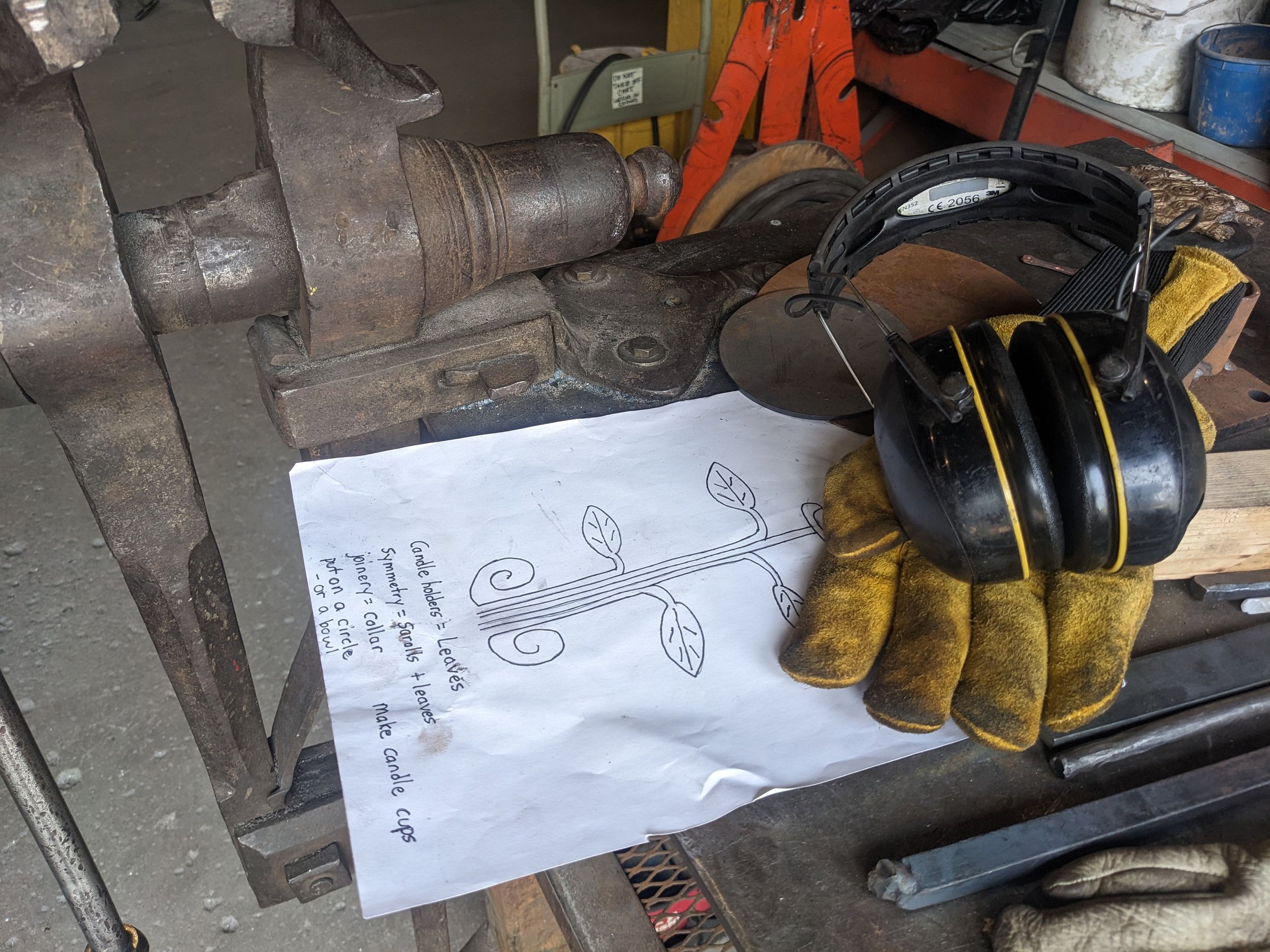

A series of tree grates, decorative panels, and sidewalk stamps were created to accompany a new residential building, known as Rivkin. The project’s original plan included a focus on alternative gardening practices and small-scale urban farming, which appears in Sayge’s designs as stylized leaves and nature-inspired patterns.

One of the tree grates installed outside the Rivkin building. Sidewalk stamps with similar motifs are visible in the background.

Sayge is an accomplished visual artist–with experience crafting ceramics, painting murals, and everything in between–but working with metal is still relatively new to them. That’s where CAFAC comes in.

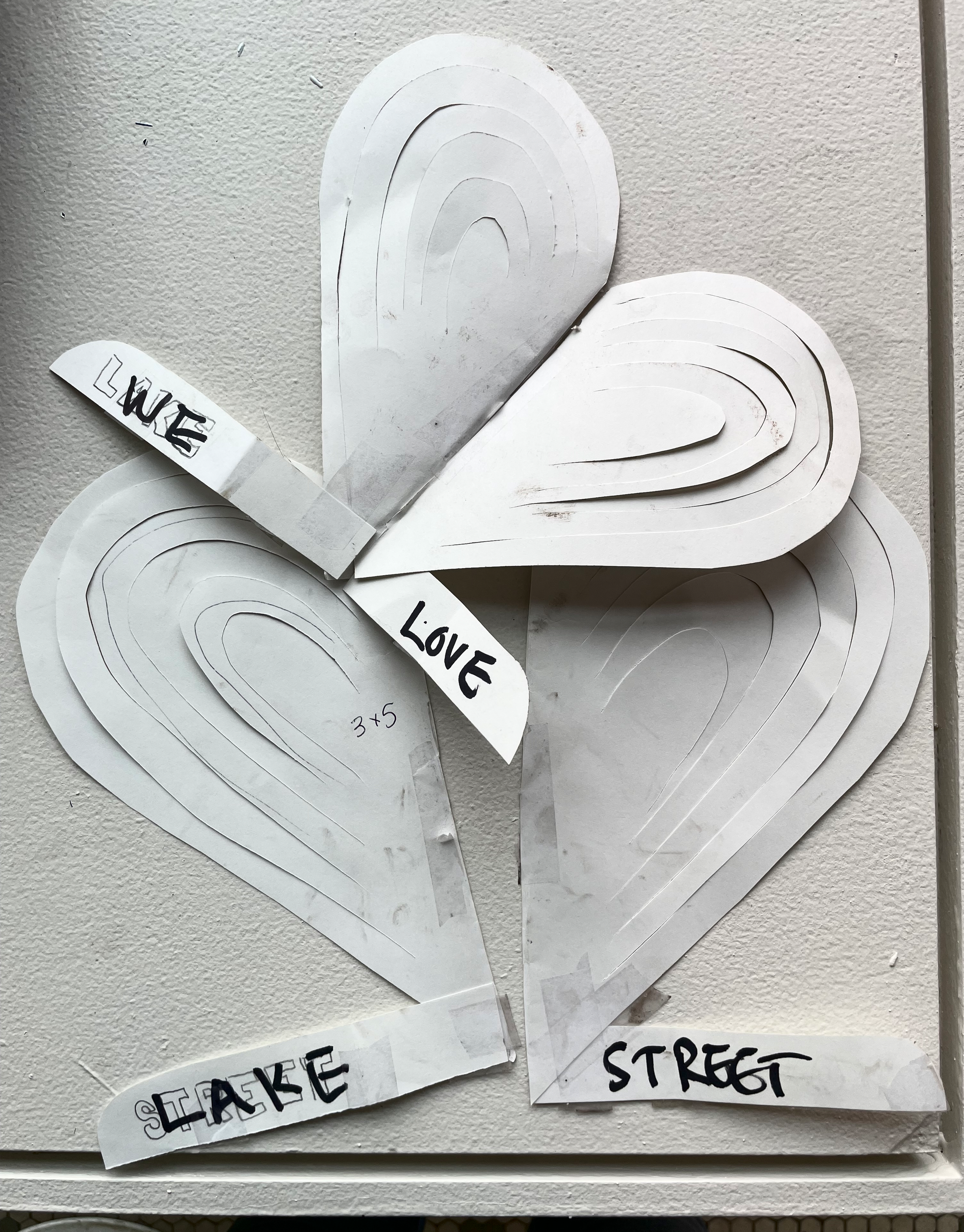

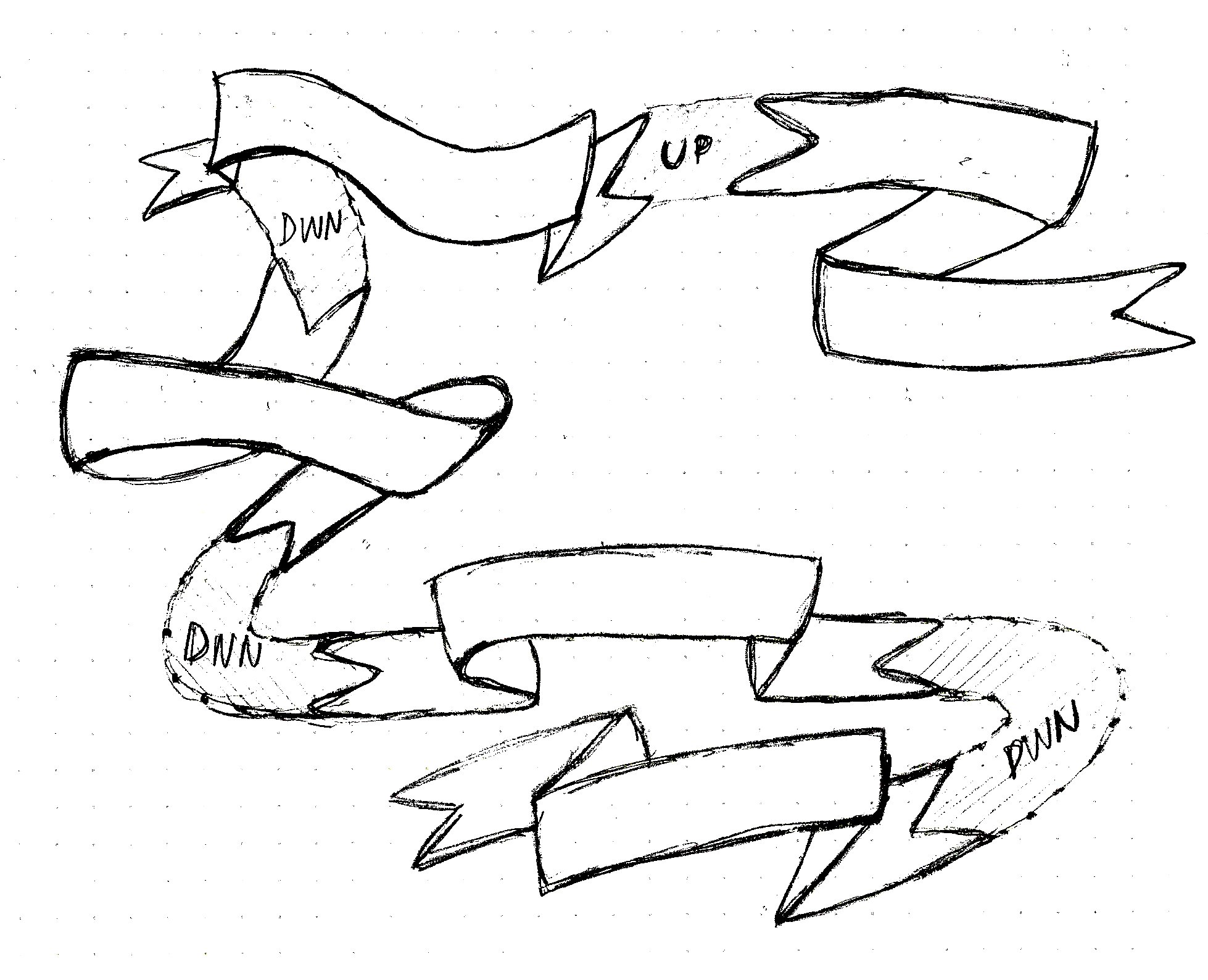

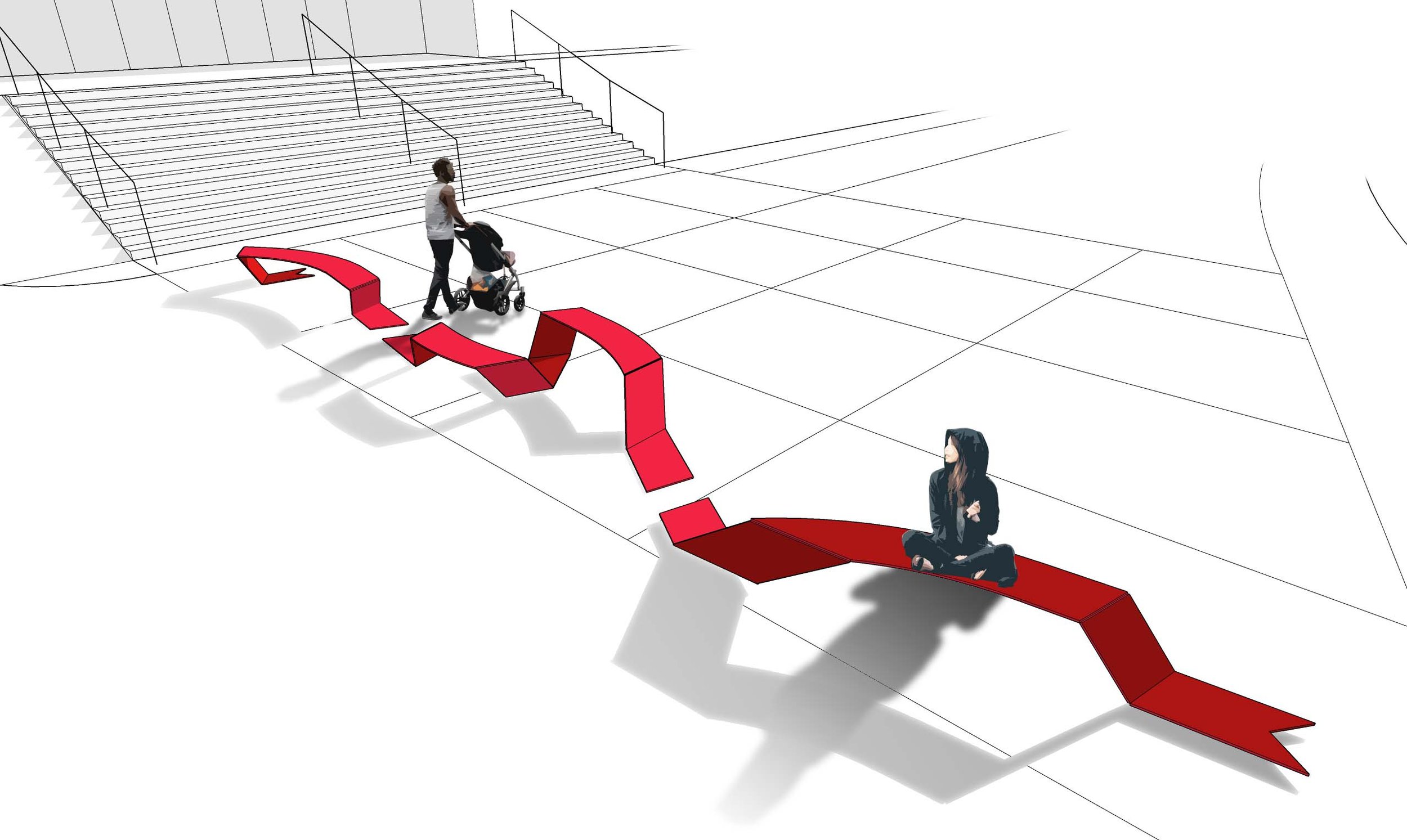

“[Heather] is just so capable of doing those things that go above my head,” Sayge laughs. “I trust her to tell me if something’s not going to work.” With a little back and forth, Sayge created designs for tree grates, decorative balcony panels, and sidewalk stamps. Fabricating these pieces out of weathering steel needed machine precision–that meant turning their hand-drawn sketch into files that could be cut on a CNC plasma cutter. By using this machine, the fabrication team could avoid the inconsistencies that come with cutting metal by hand.

“Using my hands is where I thrive, but having access to a CNC machine really catapults you [to another level],” says Sayge.

One of the decorative panels, just after being cut on a CNC table.

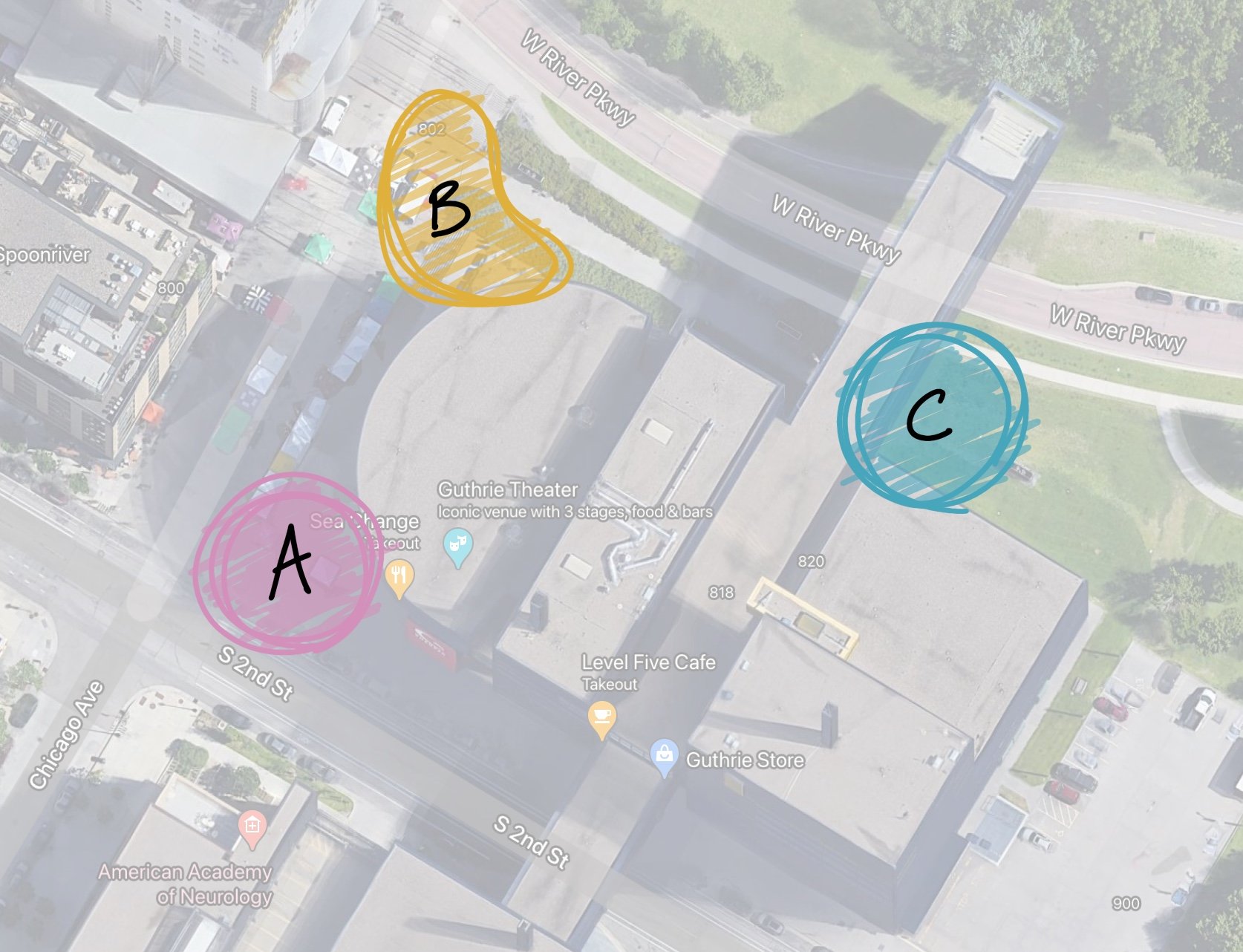

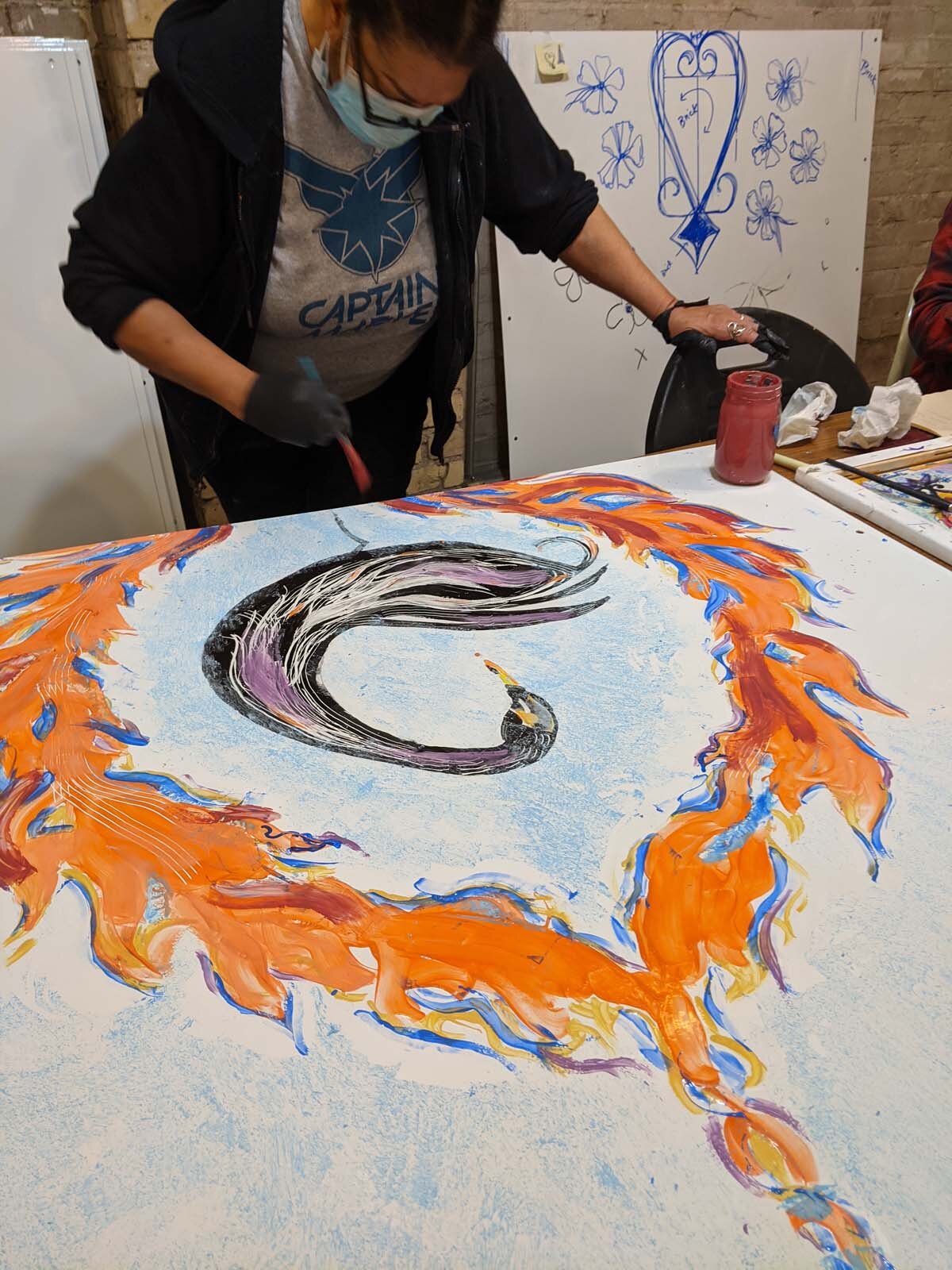

The Rivkin development is unique in having a strong focus on community building between new residents. Along with the existing sculptural work, Sayge will have a hand in running community artmaking workshops focused on tile-making. This kind of community engagement is super familiar for Sayge–in fact, some South Minneapolis residents know themas much for their annual “harvest feasts,” which ran each fall from 2016 to 2022–as for their artwork. Neighbors were invited into Sayge’s home studio to create artwork, make friends, and eat locally grown food cooked by a professional chef.

“Once we got Mudluk [Pottery] open, we haven’t been able to do [another] one,” Sayge explains. That’ll change this year with a collaborative event at George Floyd Square: the Bowls & Spoons Harvest Feast, a reimagining of those first neighborhood get-togethers led by multiple local organizations including Mudluk Pottery, CAFAC, City Food Studio, Plant-Grow-Share, and Pillsbury House + Theatre.

Shannon Brunette from the Office of Cultural Work smiles standing beside one of the installed decorative panels at the Rivkin building.

It’s only one of a range of community engagement projects Sayge is planning at the moment, however. Along with tile-making workshops for Rivkin’s residents, they’re contemplating ways to make Mudluk’s programming more accessible.

“[We’re] working on a ‘Mud Bus’ for Mudluk Pottery so that we can travel,” Sayge explains. With this ‘studio on wheels,’ staff will be able to bring their programming into the community, instead of the other way around. At the end of June, Mudluk and CAFAC will be side-by-side at the American Craft Fest in St. Paul, making bowls and spoons together with hands-on opportunities to festival-goers.

“It feels like a normal extension of community-focused projects,” says Sayge.